When calculating the risk of critical deterioration in a patient’s condition, you may not see the decline until an alarm sounds—often much too late to make a difference. However, what if you could see patient deterioration trends 24 hours before an alarm sounds? The Rothman Index predictive analytic solution can help.

Fusing clinical expertise and data science to help improve outcomes

The Rothman Index (RI) gives clinicians the ability to combine their expert clinical judgement with objective data science to drive actionable insights into overall patient condition. It’s designed to assist clinicians in early detection and intervention of deteriorating patients—to help save lives.

As an FDA-cleared artificial intelligence (AI) predictive analytics system, RI automatically extracts and analyzes constantly changing clinical measurements from the EMR, including complete head-to-toe nursing assessments. Its predictive analytic algorithms detect subtle changes over time that often go unnoticed, calculating an aggregated score of patient’s overall physiological condition.

“A deciding factor for us was the fact that the RI captures subtle changes in patient condition since it includes nursing assessments. We expected that this would set the RI apart from the vitals-based algorithm we were using.”

—Clinical Nurse Specialist/Clinical Practice Manager

RI is ideal for use across all conditions and ages and applicable in medical/surgical units, intermediate care and intensive care locations. It is useful in clinical and multi-disciplinary rounds to support:

- Decisions about proactive care escalation

- Safe downgrades to lower care levels

- Readiness for discharge

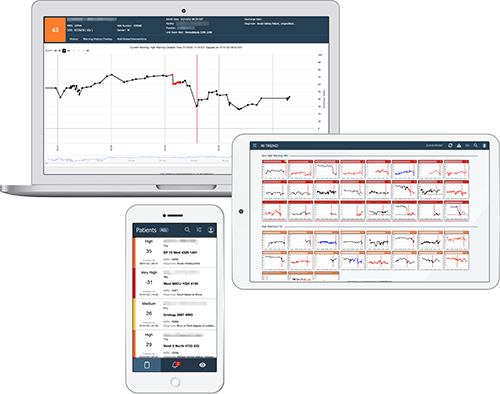

Clinicians can easily access patient level and multi-patient views via a web browser, through the EHR, or using a dedicated system-wide command center to ensure a coherent picture of the patient’s condition throughout the entire episode of care. Clinicians can review the RI graphs for all patients in the facility or unit, assess any warnings that have occurred, and select individual patient graphs to drill down into a more detailed review. The RI also tracks the patient over multiple visits, providing a retrospective view of their condition and how it is progressing.

Driving improved outcomes together

The Rothman Index has helped numerous hospitals realize improved outcomes – including small and large hospitals, community hospitals and academic medical centers. Grounded in science and validated use cases, it is supported by more than 55 peer-reviewed literature and has been attributed to:

“I handle the blue code analysis, and 70-80% of the time, the RI had identified the patients before they coded.”

— Clinical Nurse Specialist/Clinical Practice Manager

ROTHMAN INDEX TREND

Insights across the board

Detect changes before they become life-threatening, among and across patient populations, with Rothman Index Trend. The Trend dashboard can provide surveillance across all conditions, diseases and levels of care while also supporting communication during shift changes and handoffs.

ROTHMAN INDEX FOR PEDIATRICS

Tailored parameters for children

From specialized algorithms to unique software configurations, RI for pediatrics builds on the widely validated Rothman Index technology with specific adaptations tailored for pediatrics

REFERENCES

- Goellner Y, Tipton E, Verzino T, Weigand L. Improving care quality through nurse-to-nurse consults and early warning system technology. Nurs Manage. 2022 Jan 1;53(1):28-33.

- Ahmad R, Erb C. Rothman Index as a Tool to Guide Triaging to a Higher Level of Care After Rapid Response Team Activation. CHEST Annual Meeting, Oct 17-20, 2021.

- Wang L, Li G, Ezeana CF, Ogunti R, Puppala M, He T, Yu X, Wong SSY, Yin Z, Roberts AW, Nezamabadi A, Xu P, Frost A, Jackson RE, Wong STC. An AI-driven clinical care pathway to reduce 30-day readmission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. Sci Rep. 2022 Nov 30;12(1):20633.

This product is not available for sale in all countries. Please contact your local Spacelabs Healthcare representative or regional office for more information.